The Academy has separate award categories for writing: Screenplay adapted from another source and screenplays written directly for the screen. My last post is a list of movie adaptations coming out this fall/winter. In this post is a list of some highly anticipated features based on an original screenplay, all poised for the Awards Season, eyeing the 2020 Oscars race.

1917

Director Sam Mendes takes a fragment of a story his grandfather Alfred Mendes had told him and wrote this original screenplay. During WWI, two young privates (one apparently represents his grandfather) race against time to deliver a message deep into enemy territory to save 1,600 British soldiers from heading into a death trap. In real life, Alfred Mendes was given a Military Medal for his bravery in taking up the mission voluntarily. So, the movie has a particular personal meaning for the younger Mendes. The Oscar winning director (for American Beauty) has an exceptional track record of top features including Bond movies Skyfall, Spectre, and the adaptation of Richard Ford’s Revolutionary Road. In 1917, Mendes has a stellar cast to work with, including Benedict Cumberbatch, Colin Firth, Richard Madden, Mark Strong. Roger Deakins just might get another Oscar nom for cinematography.

A Hidden Life

Here’s another hero’s story but of a very different nature. This time in WWII during Nazi occupation of Austria. Franz Jägerstätter is a farmer in a small village, leading a simple and idyllic family life. Everything changes when he’s conscripted to serve in the German army. Jägerstätter refuses to take the oath of loyalty to Hitler as he considers Hitler’s war unjust and evil. Not a pacifist, but a conscientious objector due to his Christian faith. The consequence of refusing to take the oath is death. Director Terrence Malick after The Tree of Life offers us a poignant and beautiful meditation on this hidden hero, bravery no one would have noticed, on the contrary, bravery that is met with spite and hatred even by his own village folks. I watched this at TIFF and can attest that these could well be the most meaningful 3 hours in this holiday season.

Harriet

Yet another hero’s story. Harriet Tubman escaped slavery via the Underground Railroad and became an abolitionist and leading ‘conductor’, helping many slave families to freedom. During the American Civil War, Tubman worked for the Union Army in various capacities. Director Kasi Lemmons researched and wrote the screenplay with Gregory Allen Howard. This is the kind of movies where historical facts and dramatization would usually come under scrutiny. In an interview with IndieWire, Lemmons has made this statement: “Of course I embellished, I’m a screenwriter… I added to the story because anybody that’s a writer that approaches a real story has to embellish.” Cynthia Erivo plays Harriet, Leslie Odom Jr. and Joe Alwyn co-star.

The Aeronauts

British duo Eddie Redmayne and Felicity Jones reunite for another scientific venture after their Stephen Hawking biopic The Theory of Everything. The Aeronauts has these two stuck in a hot air ballon 40,000 ft. above ground. The movie is loosely based on the real-life feats achieved by James Glaisher and Henry Tracey Coxwell, who, in 1862, flew higher into the atmosphere than anyone had ever done before. For story appeal, Coxwell is replaced by the female balloonist Amelia Rennes. Looks like the dramatization of historical discoveries and scientific breakthroughs has developed into a genre of their own, such as The Current War, The Imitation Game, and Hidden Figures. Directed and co-written by Tom Harper. In N. American theatres Dec. 6 then on Amazon Prime Video Dec. 20. But looks like this one should be watched on the big screen.

Marriage Story

Back on the ground, a very realistic depiction. Noah Baumbach has written an insightful script on the dissolution of a marriage. I watched this at TIFF. Adam Driver and Scarlett Johansson deliver a superb performance as a couple going through a divorce. You’d think the process involves the husband, the wife, and the child only. But no. It looks like the lawyers are the major players in our adversarial legal system. Things get much more complicated and pricier than the couple have first thought and uglier than they’d wanted to go. Laura Dern, Ray Liotta, and Alan Alda are the lawyers, solid casting. A strong Oscar hopeful. After a limited release in theatres, this will go straight to Netflix.

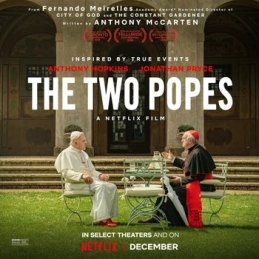

The Two Popes

For originality of a screenplay this probably is a good example. Imagine the conservative Pope Benedict XVI meeting the relatively more progressive Pope Francis I as they hang out with each other, a few years before Francis became Pontiff. Maybe a get-to-know-you, pre-screening interview for the Pope-in-waiting. Anthony Hopkins plays the conservative and Jonathan Pryce, the liberal. Helmed by acclaimed Brazilian director Fernando Meirelles whose past works include the Oscar nominated City of God and The Constant Gardener where Rachel Weisz won her Oscar. Screenplay by Anthony McCarten, 3-time Oscar nominee for Bohemian Rhapsody, Darkest Hour, and The Theory of Everything. Again, Netflix will have it after a limited theatrical run in December.

For originality of a screenplay this probably is a good example. Imagine the conservative Pope Benedict XVI meeting the relatively more progressive Pope Francis I as they hang out with each other, a few years before Francis became Pontiff. Maybe a get-to-know-you, pre-screening interview for the Pope-in-waiting. Anthony Hopkins plays the conservative and Jonathan Pryce, the liberal. Helmed by acclaimed Brazilian director Fernando Meirelles whose past works include the Oscar nominated City of God and The Constant Gardener where Rachel Weisz won her Oscar. Screenplay by Anthony McCarten, 3-time Oscar nominee for Bohemian Rhapsody, Darkest Hour, and The Theory of Everything. Again, Netflix will have it after a limited theatrical run in December.

***

Related Posts:

Movies Based on Books in Nov. and Dec. 2019